How Hamas Exploited Israeli Soldiers’ Social Media in the Lead-Up to the October 7 Attack

Source: Asharq Al-Awsat

Executive Summary

Israeli investigations now indicate that Hamas spent at least five years systematically mining the social media activity of Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers to map bases, study routines, and even learn how to disable advanced Merkava Mark 4 tanks. This open-source collection, combined with infiltrated chat groups and traditional spying, produced highly detailed plans that helped Hamas overrun bases like Nahal Oz on October 7, 2023. The scale of the information leak points to a deep failure of operational security, culture, and oversight rather than a single technical lapse. As Israel disciplines senior commanders and reviews its failures, the case is emerging as a global warning about how modern militaries can be compromised by everyday online behavior.

Intelligence Analysis

Investigations in Israel now paint a clear picture: Hamas did not rely on a single breakthrough spy, a stolen document, or a one-time hack to prepare for October 7. Instead, it appears to have spent years patiently collecting small pieces of information that IDF soldiers themselves posted online — photos from bases, TikTok clips of training, casual Instagram posts in uniform, screenshots from WhatsApp groups, and more. These fragments were then combined with traditional intelligence methods to create an unusually detailed understanding of Israeli bases, units, and equipment.

According to Israeli media and military sources, a dedicated Hamas intelligence unit of roughly 2,500 operatives tracked the social media activity of about 100,000 IDF soldiers starting around 2018. They created tens of thousands of fake “avatar” accounts on platforms like Facebook and Instagram to follow soldiers, befriend them, and gain access to private posts. Other operatives infiltrated WhatsApp groups tied to specific units and bases, allowing Hamas to follow individual soldiers from basic training through promotions and into command roles.

What Hamas was collecting often looked harmless to the people posting it: a selfie beside a tank, a short video from a discharge ceremony, a clip of troops at a training base, a casual shot in front of a gate or bunker. But over years, Hamas analysts treated these as data points. They used them to map entrances and exits, the position of cameras, the location of armories, the layout of barracks, the location of quick-reaction squads, and the patterns of daily life at bases across the Gaza border region.

This material was then turned into practical tools. Hamas built physical models of Israeli bases and detailed maps of posts along the border. It also used 3D software and virtual reality headsets to construct simulations that allowed its elite Nukhba fighters to “walk” through IDF sites before ever crossing the border. Israeli officers later admitted that they knew Hamas had some training models, but were stunned by how precise they turned out to be.

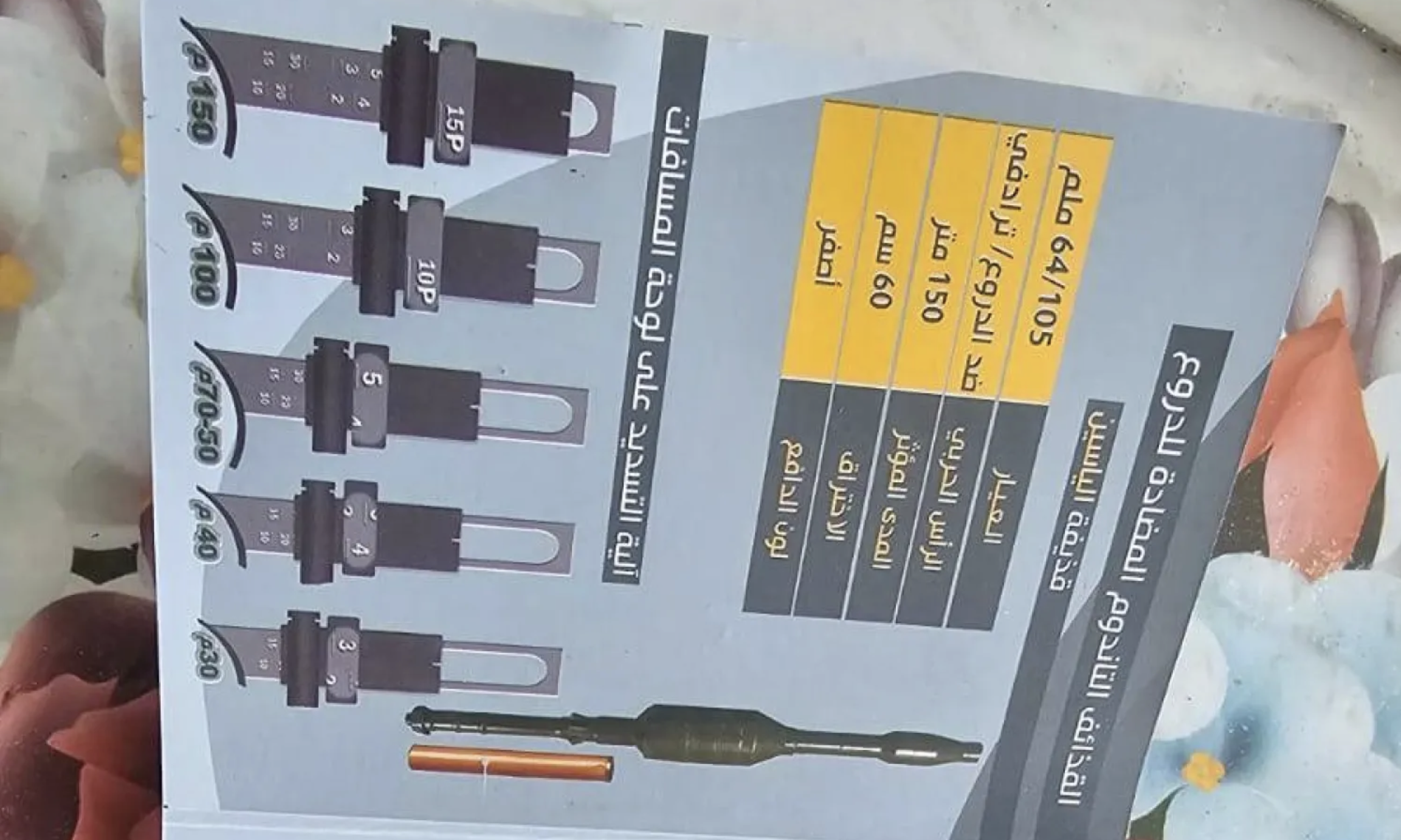

The same approach was applied to Israel’s most advanced tank, the Merkava Mark 4. Over time, Hamas collected videos and photos taken inside and around tanks at bases and training centers, including Shizafon, the main tank training facility in the Negev. Some of these videos reportedly showed soldiers demonstrating procedures or moving around inside the turret. By examining this material over a long period, Hamas intelligence appears to have pieced together how the internal systems were laid out and, critically, how to activate a hidden disabling mechanism — a “kill switch” usually known only to trained armored crews.

On October 7, Hamas fighters used this knowledge to disable Merkava 4 tanks near the Gaza border. Tanks that should have been key defensive assets were rendered inoperable at the outset of the attack and played no role in the immediate response. This puzzled Israeli commanders until early 2024, when the IDF discovered a major underground Hamas complex in central Gaza, dubbed “the Pentagon.” Inside were maps, reports, training simulators, and documentation that showed how thoroughly Hamas had studied Israeli forces using information drawn largely from soldiers’ online activity.

At the same time, newer reporting and older evidence point to a parallel track of more traditional espionage and planning. Israeli military documents captured after the attack include highly detailed maps of bases and installations that some officials say could only have been produced with inside help. Hostage-taking guides, phrasebooks with Hebrew commands, and precise plans for seizing command posts show that Hamas combined its open-source social media collection with human sources and battlefield reconnaissance.

Taken together, these findings suggest a layered approach:

Openly available social media and public content used to map layouts, routines, and equipment.

Infiltrated chat groups and fake profiles used to track specific soldiers and units over time.

Physical models, training manuals, and VR simulations used to rehearse complex assaults.

Possible inside sources and stolen documents used to refine and verify plans for key targets.

This fusion of methods enabled Hamas to treat bases like Nahal Oz as familiar terrain. After October 7, investigators found a document in Gaza that laid out the Nahal Oz base in remarkable detail: shelters, generator rooms, antennas, command posts, sleeping quarters, and weapons distribution. Probes found that Hamas knew how many soldiers were present at different times, the best time to attack, how long reinforcements would take to arrive, and optimal routes into and out of the base.

On October 7, roughly 215 Hamas fighters stormed Nahal Oz, which held 162 soldiers, only 90 of whom were armed. The attackers killed 53 soldiers and abducted 10 more, including surveillance operators who had been monitoring the Gaza border. The speed and precision of the assault suggest that Hamas forces were not improvising; they were executing a plan they had practiced repeatedly in mock-ups and simulations.

The scale of planning is further confirmed by earlier reporting that Hamas had long-term attack plans, including battle plans that Israeli intelligence had seen but discounted as unrealistic. Investigators later concluded that while Hamas spent years preparing, Israel’s security establishment did not adequately adjust its assessments of Hamas’s capabilities or intentions. Early warning signs, including unusual training activity in Gaza and specific plans, were either minimized or misinterpreted.

The fallout within the IDF has been significant. Internal investigations concluded that there were “long-standing systemic and organizational failures” and an “intelligence failure” despite access to high-quality information. The problem was not only missing data, but how existing information was assessed, shared, and acted upon. These failures extended from frontline units up the chain of command.

In late November 2025, the Israeli military announced the dismissal of three generals and disciplinary measures against several other senior officers for their roles in the failures surrounding October 7. Those reprimanded included divisional commanders and senior leaders in intelligence and operational roles. The army chief described these moves as part of a systemic reckoning with what went wrong, even as the political leadership has not yet agreed to a full state commission of inquiry.

From an intelligence and security perspective, several themes emerge:

First, social media has become a powerful intelligence sensor. Every smartphone in a secure environment is, in effect, a potential data leak. The Hamas case shows that a determined adversary can build a strategic picture not by hacking secret systems, but by patiently collecting and organizing public or semi-public posts over time. A single photo rarely gives away a base; thousands can.

Second, operational security is as much cultural as technical. Israel has rules restricting the sharing of sensitive information online, and the IDF regularly warns soldiers about what they post. But the volume and detail of what Hamas collected suggest that these rules were not consistently enforced, and that many soldiers did not see their online behavior as a serious risk. In an era where social media is deeply integrated into personal identity and daily life, traditional security briefings on their own may be insufficient.

Third, intelligence assessment bias played a critical role. Even as Hamas prepared and practiced, sections of the Israeli security establishment continued to view it as deterred and focused mainly on governing Gaza, rather than planning a large-scale cross-border attack. This mindset made it easier to discount warning signs and to underestimate the potential value of Hamas’s training models or open-source collection.

Fourth, accountability is extending beyond frontline failures to senior leadership. The dismissal and reprimand of senior generals signal a recognition that failures were not simply at the tactical level. However, the lack of a comprehensive civilian-led inquiry so far leaves open questions about political responsibility and the broader national decision-making process before October 7.

Looking ahead, this episode has implications well beyond Israel:

Other militaries and security services will likely revisit their social media policies, not just on paper but in enforcement, training, and monitoring. The central question is how to balance soldiers’ personal lives with the realities of a digital battlefield where every post can be weaponized.

Non-state armed groups worldwide may see Hamas’s approach as a model. The perceived success of using publicly available data, cheap simulation tools, and patient analysis could inspire similar efforts by other groups with limited resources.

Governments and private-sector organizations with sensitive assets — such as critical infrastructure, defense contractors, and security agencies — will need to consider that their personnel’s public footprint can be systematically mined by hostile actors, even if no internal systems are breached.

For Israel specifically, there will likely be long-term reforms in how intelligence about adversaries is collected, analyzed, and challenged, and how digital behavior by soldiers is regulated. The dismissal of generals is a step, but reshaping a security culture that missed these signals will take years.

Ultimately, the October 7 failures cannot be explained by social media alone. Hamas combined open-source collection with traditional spying, tactical innovation, and a willingness to absorb heavy losses. But social media acted as a force multiplier, turning everyday posts into tools for planning one of the most devastating attacks in Israel’s history. For security professionals worldwide, the lesson is stark: in the age of smartphones, operational security is no longer confined to classified systems and guarded fences. It lives in the apps, habits, and assumptions of every person in the chain.

Analyst Note

The Hamas case is a reminder that “open-source intelligence” is not just something states do to each other; it is now accessible to any organized group with time, patience, and basic technical skills. That reality lowers the barrier to sophisticated planning and makes human behavior — not just technology — a central vulnerability.

Sources

The Times of Israel – Hamas spent years mining IDF troops’ social media for intel on bases, tanks

The Jerusalem Post – Hamas used fake Instagram profiles to map IDF bases, track soldiers before October 7 assault

Israel National News – This is how Hamas disabled tanks near Gaza on October 7th

Asharq Al-Awsat – How Hamas Learned Secrets of Israeli Merkava Tanks

The Guardian – Hamas drew detailed attack plans for years with help of spies, documents suggest

Asharq Al-Awsat – Israeli Military Sacks Several Generals Over October 7 Attack