Chinese-Owned Property Networks Near U.S. Bases Signal a Growing Counterintelligence and Infrastructure Risk

Executive Summary

Property, retail, and resource holdings tied to PRC-linked individuals and companies—ranging from a trailer park a mile from Whiteman AFB to retail concessions on U.S. military bases and farmland near sensitive installations—underscore a widening counterintelligence and critical-infrastructure exposure. If the Missouri ownership chain and related Canadian links are verified, they would fit an established pattern: opaque corporate structures, diaspora-adjacent influence activity, and targeted acquisitions proximate to defense nodes and critical minerals—outpacing current screening and enforcement mechanisms.

Key Judgments

Key Judgment 1

The reported PRC-linked ownership of a trailer park abutting Whiteman AFB, if substantiated, would represent a high-leverage, low-visibility foothold for surveillance or disruption options.

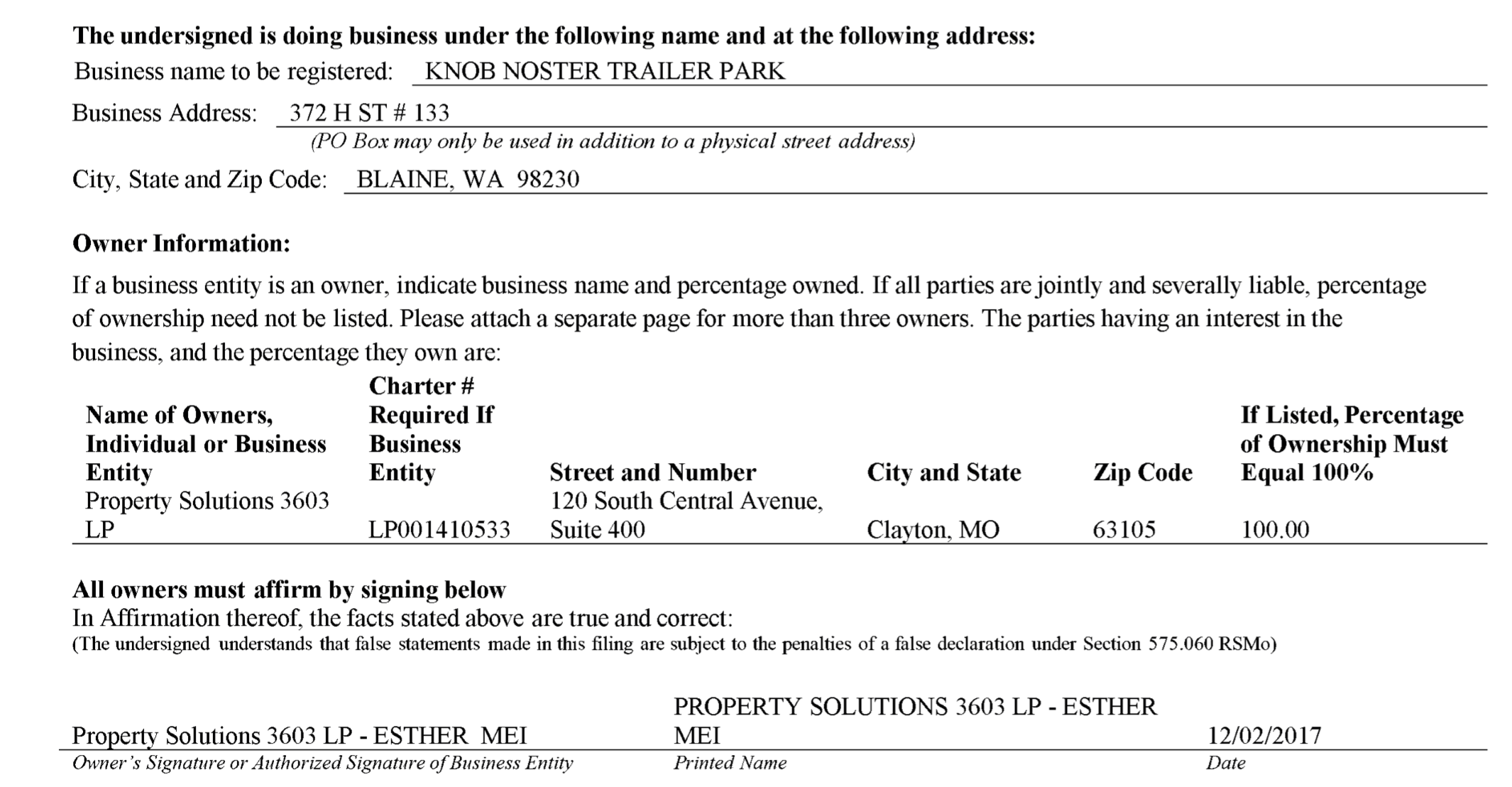

Evidence: Corporate and permitting records assembled by U.S. media identify a shell-entity chain owning the Knob Noster Trailer Park roughly one mile from Whiteman’s runway and link it to a Richmond, B.C., couple already named in Canadian civil filings related to New Federal State of China (NFSC) activities.

Key Judgment 2

Cross-border connective tissue—Vancouver-based actors, NFSC activism, and litigation trails—creates plausible adjacency between influence networks and U.S.-side physical assets.

Evidence: B.C. court records and reporting associate the Richmond residents with NFSC demonstrations targeting journalist Bingchen Gao; U.S. filings list Vancouver entities among defendants in Guo-linked cases, while U.S. reporting details the couple’s business ties.

Key Judgment 3

The broader landscape of PRC-linked proximity—retail concessions on bases, farmland purchases near installations, crypto-mines, and mysterious large-scale land aggregations—has outpaced fragmented U.S. oversight.

Evidence: Congressional scrutiny of Chinese-owned GNC stores on bases; multiple cases of farmland near bases (e.g., Fufeng in Grand Forks); White House-ordered divestment of a Chinese-backed crypto-mine near F.E. Warren AFB; and unresolved concerns around large purchases near Travis AFB.

Key Judgment 4

Existing legal and regulatory tools are necessary but insufficient: CFIUS geography gaps, lagging USDA disclosure data, and uneven state restrictions blunt timely risk mitigation.

Evidence: CFIUS jurisdiction limits in Grand Forks; USDA’s self-reported, delayed agricultural ownership data; a patchwork of state-level bans, with parts enjoined by federal courts on constitutional grounds.

Analysis

The Missouri case—shell companies tied to a Richmond, B.C., couple reportedly controlling the Knob Noster Trailer Park within a mile of Whiteman AFB—should be evaluated through a risk-based, not intent-based, lens. Proximity to a nuclear-capable stealth base that launched strikes in June 2025 is inherently sensitive. Trailer parks and low-profile commercial parcels offer physical access, line-of-sight, and cover for benign activities that can mask passive technical collection, human observation, and logistics staging. Layer on the opacity of limited partnerships and cross-jurisdictional registrations, and the result is a hard-to-penetrate beneficial-ownership picture—precisely the scenario foreign services cultivate.

The Canadian dimension matters. Litigation and video records tying the same couple to NFSC street activities in Vancouver—amid a broader controversy around Miles Guo, now convicted in the U.S.—extend beyond mere coincidence. While activism is not espionage, overlapping networks, fundraising vehicles, and shell entities create channels through which state-adjacent actors can recruit, task, or exploit. Historical Canadian cases reinforce the pattern. Su Bin’s Richmond-based cell hacked U.S. aerospace programs for years before arrest, highlighting the latency between activity and disruption. Scholarly work on the United Front in Canada documents political influence and industrial targeting that often arcs south.

Zooming out, the Whiteman report is not an outlier but part of a mosaic. On-base retail concessions owned by a PRC-controlled parent (GNC) expose personnel data, purchase patterns, and cyber surfaces. Farmland acquisitions near bases—Fufeng in North Dakota being the archetype—demonstrate how CFIUS real-estate jurisdiction gaps can leave sensitive perimeters exposed. Large, unexplained land assemblies near Travis AFB underscore the stakes where ownership opacity persists. Crypto-mines located near missile and bomber bases present dual risks: intelligence collection and grid stress/sabotage vectors. Meanwhile, aggregate foreign agricultural land ownership data remain delayed and under-enforced, limiting strategic mapping.

U.S. policy responses are evolving but uneven. Congress is pushing to expand CFIUS real-estate coverage and tighten USDA reporting, while states enact foreign land-ownership bans—some colliding with federal law and constitutional protections, as Florida’s partial injunction shows. This patchwork invites forum-shopping. Without unified beneficial-ownership transparency and consistent national-security reviews across retail concessions, farmland, utility interconnects, crypto facilities, and adjacent commercial properties, adversaries will keep exploiting seams.

For operators and policymakers, the immediate priorities are clear. First, verify Missouri beneficial ownership chains, financing flows, and control rights; if necessary, trigger CFIUS or other federal authorities via expanded “covered real estate” designations. Second, implement near-base “defense critical infrastructure zones” with enhanced reporting, signal-emission monitoring, and zoning overlays that flag or prohibit sensitive acquisitions regardless of land use. Third, mandate beneficial-ownership disclosures for any concessionaire operating on DOD installations and for vendors with persistent digital interfaces (apps, loyalty programs, Wi-Fi). Fourth, accelerate USDA’s electronic, real-time agricultural land database and harmonize penalties to deter non-reporting or misreporting. Finally, deepen cross-border coordination with Canadian counterparts on beneficial ownership registries, NFSC-linked entities, and critical-minerals plays—particularly where lithium or other strategic resources intersect with United Front-adjacent networks.

Bottom line: the question is not whether each node is definitively controlled by Beijing, but whether the cumulative, plausibly deniable footprint near America’s most sensitive assets creates intelligence and disruption options at scale. On current trajectory, the answer is yes.

Sources

CBS News – How China could use U.S. farmland to attack America (60 Minutes)

Counterterrorism Group – Are Chinese entities buying farmland near U.S. military bases?

NPR – China owns 380,000 acres of land in the U.S. Here’s where

ABC7 News – $800M land purchase near Travis AFB prompts legislation, concern over foreign threat

CNBC – Chinese company’s purchase of North Dakota farmland raises national security concerns

Reuters – U.S. court blocks Florida law barring Chinese citizens from owning property